Ever since hordes of Americans began fleeing big coastal cities during the pandemic, I’ve been wondering when — or if — they’d return. Sure, things are less expensive in the places they moved to, and the quality of life is often higher. But more and more, urban refugees have been pining for the things they left behind, from culinary excellence to cultural diversity. Every week it seems like I see a new story about some former San Franciscan or New Yorker regretting their decision to leave.

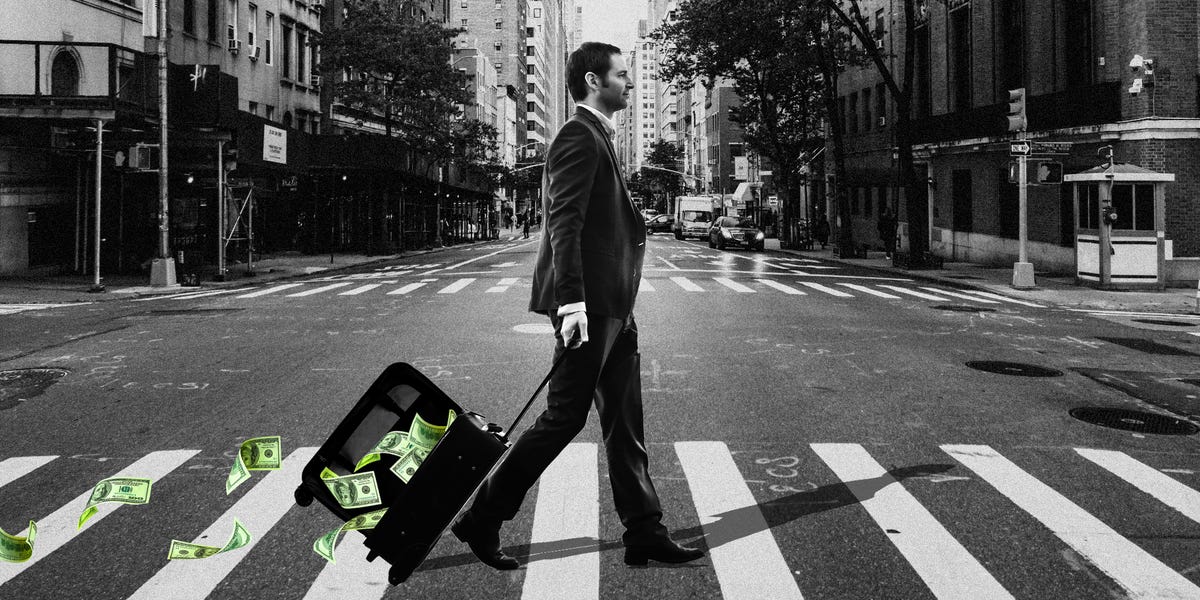

So recently, when the Census Bureau released its new estimates for domestic migration, I thought we were finally going to see a reversal of the big-city exodus. But I was wrong. From mid-2022 to mid-2023, the bleeding in many big metropolitan areas continued. New York lost 238,000 more people than it gained. The numbers read like casualty reports: 155,000 in Los Angeles, 54,000 in San Francisco, 25,000 in Seattle. Granted, the urban flight isn’t as bad as the crisis-level hemorrhaging we saw in the first year of the pandemic. But every day, hundreds and hundreds of people continue to forsake America’s greatest cities for smaller, more affordable destinations.

We’ve heard a lot about how the mass migration has been bad for major cities, sending them into a “doom loop” of empty offices and shuttered storefronts. But a new paper coauthored by Enrico Moretti, one of the best thinkers on the geography of jobs, highlights the dangers the migration poses for the very professionals who are ditching big cities. Moving away from a major city, Moretti found, can be terrible for your career.

Moretti, an economist at the University of California at Berkeley, followed workers whose companies shut down between 2010 and 2017. How people fared after that depended on where they lived. Those who lived in small labor markets were less likely to find a new job within a year than those in large labor markets. To get back on their feet professionally, those in small markets were more likely to be forced to relocate for employment. They were also more likely to settle for a role that was misaligned with their college degree, or in an entirely different industry.

“The big takeaway is that market size matters,” Moretti says. “It’s clear that larger markets improve the quality of the match.”

That’s precisely why workers and the companies that employ them tend to cluster in the same cities. Economists call it agglomeration. Let’s say you’re a coder specializing in AI. You’re far more likely to find a job in San Francisco than you are pretty much anywhere else in the world, because there are a lot of AI-related companies there. And it’s because AI specialists flock to San Francisco that AI businesses set up shop there in the first place. That’s how cities become hubs for particular industries, like finance in New York and fashion in Paris. And that’s why people put up with all the downsides of cities — because it increases their odds of growing their careers. Moretti’s new paper confirms that when it comes to jobs, geography is destiny.

At first it seemed as though the pandemic had rewritten that rule. With the rise of remote work, professionals thought they could afford to leave their expensive cities without a risk to their careers. If you moved to Des Moines and wound up losing your job, you could just stay put and get another work-from-home gig. Your house might be in Iowa, but your job market was still back in California or New York.

But over the past year, more and more employers have stopped hiring for remote roles. The market for WFH jobs has cratered, putting everyone who moved away from big cities at risk. If they wind up getting laid off or they outgrow their current role, living in a smaller job market is going to severely limit their career options. As Moretti’s paper shows, they’ll either (1) wind up unemployed for a long stretch, (2) be forced to settle for a local job they’re overqualified for, or (3) have to make an abrupt and costly move back to the big city they abandoned.

Moretti characterizes being in a large labor market as “insurance” against future shocks. Living in a big city isn’t just about having a good job right now. It’s what sets you up for success to land your next job — and the job after that. Those who moved away from big cities effectively gave up their career insurance.

And that’s not all they gave up. When you live in an industry hub, you’re surrounded by professional peers, making it easier for you to accumulate knowledge and skills. That’s not just because you get to collaborate in person with your coworkers every day. In a big city, you also run into people who work for other companies in your industry — on the bus, at the bar, in line at the deli. Those serendipitous conversations not only expand your professional network, they also create what economists refer to as “knowledge spillovers,” helping you learn new stuff that’s relevant to your work. That’s why innovation, as measured by patents, is higher in large markets, and why businesses in big cities tend to have higher productivity.

These upsides to living in a big hub are less obvious than the low rents and nice homes that have lured so many professionals to smaller cities. They also take time to manifest — you have to lose your job before you realize how hard it will be to find another. So professionals haven’t come to grips yet with what they gave up by moving away. “The benefits of being a big city,” Moretti tells me, “have been underappreciated” during the pandemic.

Until recently, I was one of those underappreciators. In 2021, my remote job allowed me to move from San Francisco to Sacramento for my then-wife’s job. We could suddenly afford a spacious two-bedroom in an apartment complex with a pool, and I loved the slower pace of life. Even after we split up, my initial plan was to stay in Sacramento. But as I started driving into San Francisco more often to meet with sources in the tech industry, I realized that being in the city was helping me come up with better story ideas. So a few months ago, I moved back to the Bay Area. Being here makes me better at my job. And if I should lose my job at some point, I know my search will go much better here, where there are more journalism jobs, than it would if I had stayed in Sacramento.

Of course, lots of professionals who left big cities during the early days of remote work will stay where they are, even if they lose their jobs. After all, one of the other trends spurred by the pandemic was the realization that career isn’t everything. Plenty of people will be happy to settle for a lesser job if it means they don’t have to sit in soul-crushing traffic and can have a big backyard for their kids.

But Moretti thinks the exodus from big cities is nearing an end. As the outward migration slows, he predicts, new people looking for career opportunities will flood into urban areas, more than making up for the people who left. The big hubs will resume agglomerating, just as they did in the decades leading up to the pandemic. Cities, in short, will be cities again.

“It’s more a matter of when than if,” Moretti says. “I never thought this was going to be a permanent change in the geography of labor.”

Madison Hoff contributed reporting.

Aki Ito is a chief correspondent at Business Insider.